I've been pondering on the theme of the Church in the city, specifically the church building, along these lines:

|

| The Cathedral in Bristol, UK |

Furthermore churches - to varying degrees - hosted the life of the city physically as well as spiritually: markets, court hearings, daily politics were conducted in their precincts.

2) Nowadays the opposite is the case. Churches exclude the quotidian business of the city and are largely excluded from the places it is conducted except, perhaps and in some places, for ritual and long-since-forgotten historical reasons. Whether they continue to dominate the skyline - or not - churches are now left as largely empty spaces visited by tourists and devotees.

For the most part this is a matter of regret and anxiety, not least financially. The Roman Catholic Church and the Church of England, and no doubt others, still remember in their bones and their ordering the days when they were at the heart of the city and the loss of this position still pains them. Bishops continue to be titled after cities. Cathedrals remind them of the place they have lost. The Pope may still address Urbe et Orbe.

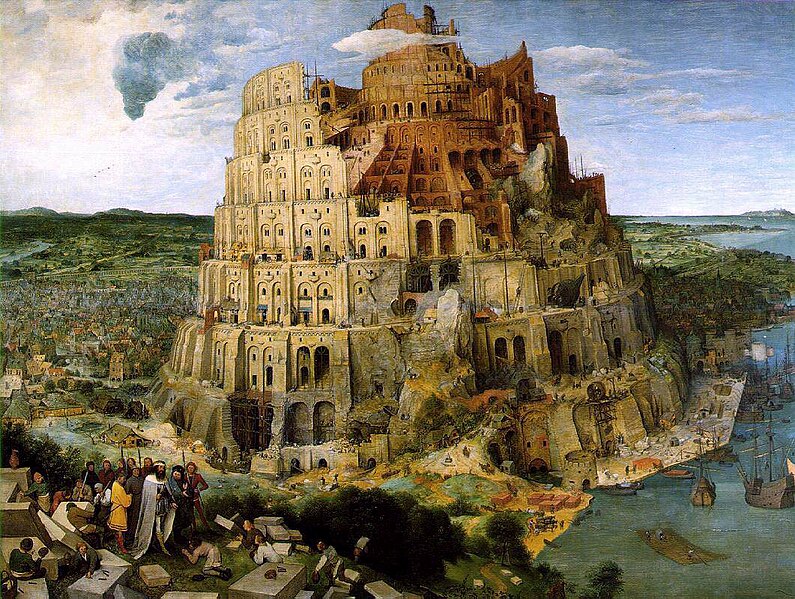

3) But the city is in many ways antithetical to the divine ordering of creation. (This largely from a superficial reading of Jacques Ellul’s The Meaning of the City). Cities order themselves by their own logic: once for warfare and now for commerce. Most profoundly they set themselves against God by their hubris: they are engines of human self-sufficiency and self-legitimation and, like Babel, they aspire to touch heaven by their own efforts (taking heaven here as a secular metaphor).

|

| Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Tower of Babel |

Churches are not, of course, entirely empty (leaving the redundant aside, by definition). They are in fact alternative places: where death is not shunned but articulated, where an alternative to urban self-sufficiency is articulated, where people may receive help because they are in need, where there is quiet and healing and people are valued merely because they are children of God. They are places of prayer and worship through which we continuously re-orientate our relationship towards God.

The deliberate differentness of a church is inherently counter-cultural: the in-group language and concepts, the endorsement of dissentient values, strange ritual behaviour, clerical clothes and odd patterns of singing. It delights and puzzles me that (some) Christians who read newspapers that are deeply, even viciously, antagonistic to immigrants will still give money, food and time to support asylum seekers. The spiritual narrative of Christian faith, of self-giving, of death and the hope of resurrection, is deeply opposed to the narratives of success and value dominant in the city.

Church buildings may also be reversing mirrors of certain specific places in the city. The opposite of a prison or court cell – insofar as Christian practice is the opposite of policing and judgement. The opposite of databanks and the secure vaults of traditional banks – Christian knowing is indestructible (though not immutable), Christian treasures are not of this world and Church doors are (nominally) open to all. Churches are the opposite of secret places in people’s homes where trafficked women are kept enslaved. Churches are places of non-violence.

Christians and church structures are deeply conformist and have a strong tendency towards conservative social and political views and values. Yet the place that they value, because it is a place for prayer, is inherently a subversive space.

No comments:

Post a Comment