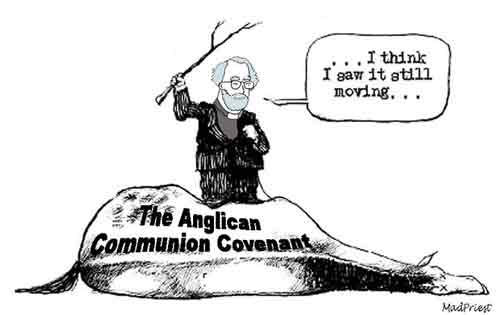

Suddenly there's a little flutter of

pro-Covenant publicity. Clearly the

No Anglican Covenant Campaign has got people rattled.

There is one very good reason why those who want the Covenant have been so tardy in asserting their case: serious opposition was never expected.

I am confident that there was a conscious policy of

not provoking discussion, of

not dealing with the issues or the detail. I believe that the planned tactics have been to assert the merits of the Covenant in bland and general terms and to repeat

there is no alternative. The calculation was that if this twin message was reiterated often enough, people would be lulled into passing the Covenant on the nod.

Reception of the Covenant

Hence the new talking-heads videos described as "

empty of critical content" by Mark Harris. They come from a sub-group of the Inter-Anglican Standing Commission on Unity Faith and Order (IASCUFO). This group is tasked with facilitating the reception of the Covenant across the Communion.

But, please note, this is reception

after the Covenant has been adopted. It was never anticipated that the group would need to explain or justify the Covenant in order to convince the voters of each Province to vote in favour. Here 'reception' means a PR exercise to induce people to like the Covenant once it was a legal fact that they could do noting about. (Admittedly 'reception' has always been a poor starveling in the spectrum of Anglican ecclesiology.)

Therefore the tone of the videos is mellow and reassuring: the Covenant is entirely benign, a Good Thing, motherhood-and-apple-pie, so don't worry your heads over it.

This is the Covenant of fairy land. It is as though

To Mend the Net had never been written or GAFCON created, as though Gene Robinson had never been consecrated bishop, as though no same-sex couple ever had their union blessed in church, as though there had never been any intrusion by one Province into the territory of others, as though Primates have always shared bread and wine together without demur, as though no Province had already declared itself out of Communion with any other.

|

The Rt Revd Kumara Illangasinghe

Bishop Emeritus of Kurunagala

|

References to any of this are child-like in their blandness: 'challenging times', 'some differences and some challenges', 'difficulties', 'some kind of opposition to some of the things that we are trying to do', 'there may be times of differences and concerns that could create some measure of dissension or disturb the peace'.

The one near-exception is the video in which Bishop Kumara Illanginghe compares events in the Communion to civil war in Sri Lanka. He starts by saying of Sri Lanka that 'our agony' has been that 'we have failed to deal with the causes that led to the war'. Yet he makes no attempt to address the causes of the civil war in Anglicanism. Instead he leaps to mutual accountability. This is surely a missed opportunity.

So, tell us about this Covenant ...

So far as I can work out the PR message is 'we need this Covenant'. The reasons are:

Q) How can Anglicanism resolve its identity crisis?

A) The Covenant articulates more clearly than before what Anglicans hold in common.

Q) How can we avoid division?

A) Sign the Covenant.

Q) What is the Covenant?

A) It is a constitution for the Anglican Communion. A reminder of our common life together. A means to resolve dissension for the smooth operation of the Communion. An aid to our mission.

Q) What form should our unity take?

A) Be accountable to one another and committed to each other by checking out decisions with one another. This is explicitly associated with the will of God. Deepen and strengthen our partnership. Be more Christian and more charitable. Some are concerned about the Covenant, especially section 4, 'as having to do with external control and authority': this is not well founded, but understandable.

Q) What will be changed by the Covenant?

A) Nothing: no new tests of doctrine, belief or ethical standards.

|

The Rev'd Dr. Katherine Grieb,

Professor of New Testament,

Virginia Theological Seminary

|

Katherine Grieb implies (though her language of 'false choices' leaves a lot of wriggle-room) that TEC will continue to be able elect gay partnered bishops, that we could 'work towards' blessing same-sex marriages (she doesn't say continue to do so in the mean time) and she wants, in the future, 'to work things out in ways that are acceptable to everyone'.

This beggars belief. If it's true then no conservative Province will sign. If it's not true then it's duplicitous. And to subordinate local change to universal agreement means making oneself a hostage to everyone else's prejudices, a recipe for disaster for all concerned.

So let's all sign up?

The immediate and obvious problem with these presentations is that they are aimed at reassuring those who are already on board or who know nothing about the Covenant.

They don't address the text in any detail. They don't explain the context of organizational change in the component parts of the Anglican Communion. They don't acknowledge the sanctions embedded in Section 4. They don't specify the entailed changes in relations between Provinces or between Provinces and the central organs of the Communion except by the bland phrase: 'mutual accountability'. Any 'concerns' that they acknowledge are simply denied.

Nor do they specify what is wrong with the present arrangements. In the absence of a clear description and diagnosis of the wrongs and inadequacies of the present Communion there is no way to judge whether this particular Covenant is going to redress any of the issues. Nor is there any discussion of what might be changed or lost as a result of implementing the Covenant.

So, take my advice, don't buy a pig in a poke.

An afterthought:

Oh, and there's one last small but perfectly formed symbol of the relationship between those preparing the 'reception' of the Covenant and the rest of us. It's a statement tucked underneath each clip: 'Adding comments has been disabled for this video.'