I wrote this for another context but it seemed worth repeating here, with a few corrections and some footnotes.

I wrote this for another context but it seemed worth repeating here, with a few corrections and some footnotes.--------------------------------.

Church and State: the Church of England's capacity to determine its own worship and doctrine.

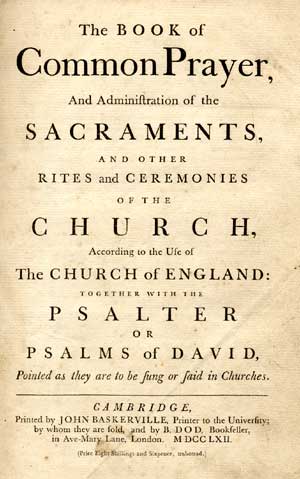

Until 1965 the CofE had no legal power to alter its own worship [Note 1]. There was a revised Prayer Book in 1928/29. Parliament refused to authorise it and after a major row Church-and-State row the bishops issued a statement that they would never sanction prosecution of clergy who conducted worship within the parameters of the revised book and no-one tested it legally [Note 2]. A revised book (again, technically illegal) was published in 1945 on the personal authority of Archbishop Fisher.

In 1961 the New English Bible was published and enthusiastically welcomed by clergy. However, legally, they could not use it in the Eucharist as the reading were printed in the BCP which could not be changed. A Measure (Church law authorised by Parliament) was prepared to allow the New English Bible to be used as an alternative to that printed in the BCP. [Note 3]

However, while this was in preparation, negotiation between the Church and the government of the day suggested that the Government would allow 'delegated legislation' i.e. Parliament delegated to the Church the power to determine its own worship - but only for a limited, experimental period of 2 to 7 years - in the Prayer Book (Alternative and Other Services) Measure.

That experimental period (taking 14 years) produced Series 1, 2, 3 styles of worship. In 1974 the Doctrine and Worship Measure gave the Church further powers which led to the Alternative Service Book 1980 (to give it its full title - the date showed it was meant to be temporary). This was valid for a decade and then a second decade's life was added. The original intention had been to produce a single New Book of Common Prayer which Parliament would have been asked to authorise and which would have been set in legal stone.

That experimental period (taking 14 years) produced Series 1, 2, 3 styles of worship. In 1974 the Doctrine and Worship Measure gave the Church further powers which led to the Alternative Service Book 1980 (to give it its full title - the date showed it was meant to be temporary). This was valid for a decade and then a second decade's life was added. The original intention had been to produce a single New Book of Common Prayer which Parliament would have been asked to authorise and which would have been set in legal stone.

But the Church had pulled off a coup: the temporary delegation of powers was finessed into a permanent delegation. The Church acquired - for the first time in its history - the power to determine its own worship.

The Doctrine and Worship Measure also gave the CofE power over its own doctrine. Thus was tested in law in 1994 and again in 1996 [Note 4] over the question of the ordination of women. The court determined that, so long as the Church followed its own rules in making doctrinal decisions (explicitly or implicitly), there was no legal power to interfere in the substance of those decisions.

This autonomy was gained, critically, without the Church ceasing to be the Established Church. It was an invisibly amazing achievement: the goal had first been articulated in 1840 or 50 and it had been pursued for 120+ years.

And the relevance of this to a Covenant is:

(a) because the CofE is a State Church it has no ecclesiology - it has had no capacity to think for itself what kind of church it is and should and could be,

(b) the CofE has had centuries of training in the arts of being subordinate and acting as though it was autonomous - it exists through a sophisticated systemic exercise of willful blindness and realpolitik.

(c) The point at which it acquired the power to determine its own doctrine was too late for it to exercise such power. From the mid-1980s ecumenical agreements and the changing shape of the Anglican Communion meant that in practice it could only make definitive doctrinal statements in concert (if not uniformly) with other churches and the rest of the Communion - see, for example, the statement on Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry.

So to adopt the Covenant for the CofE would simply be to accept a new overlordship while continuing to pretend it is superior to it. It will make sure its officers are embedded in the operation of the Covenant so that nothing potentially embarrassing comes to the light of public debate. And thus it will ensure it still doesn't have to think about its ecclesiology - what principles - actually and ideally - underlie, predispose and can be used to judge the words, structures and action of the Church of England?

========================

Notes:

1. ‘... a clerk has no right in performing divine service to alter, omit, or add anything to the prescribed form, including the lessons to be read.’ Ecclesiastical Law, reprinted from Halsbury’s Laws of England, Third Edition, (London, Butterworth & Co., 1957)

2. "... the Upper House of the two Convocations, with the acquiescent cognisance of the Lower Houses, recommended, with only four dissentients, that the bishops should not, in their administration, feel bound to interfere with clergy whose deviations from the Book of Common Prayer were within the limits of the deviations which the Prayer Book Measure of 1928 would have sanctioned." Church & State: Report of the Archbishops’ Commission on Relations between Church and State, 1935 (London, The Press and Publications Board of the Church Assembly, 1935) [The Cecil Report], p. 39.

3. In the first version of the Prayer Book (Versions of the Bible) Measure no other version of Scripture was to have been permitted. But, on a steer from the Government, the Measure was redafted to permit any versions which Church Assembly (General Synod's precursor) might approve. It became law in 1965.

4. The case (in fact a series of cases) was brought by a Rev. Williamson whose persistence led to him being formally barred from further action as a 'vexatious litigant' in 1997. The nineteenth century had several examples of the same process: convinced litigants brought cases which only strengthened the causes they were arguing against.

See also: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alternative_Service_Book

This is a good point. A number of us have wondered whether to sign up to a binding Covenant and cede powers to a 'foreign' oversight might not be unconstitutional for the Church of England?

ReplyDeleteIn any case the Covenant is a 'knee-jerk' reaction to deal with a crisis in the Communion - one of many over the years that have otherwise been resolved, albeit in a messy way.

The problem is that the present Covenantal proposals will lock us into a position of no change forever. They will give enormous power to a small group, allow other Provinces to interfere in geographical areas that are not their own, change the Communion into a Lutheran type of confessional Church and formalise a probable three-way schism.

The North Americans won't sign up. The schismatics and their Equatorial African/South East Asia supporters can't sign up and the rest will sign up out of resignation or loyalty to Rowan Williams who has put so much effort into the idea.

Much depends on the English General Synod but should it vote against (after inevitably referring it to the dioceses) Rowan Williams will have no choice but to resign.

Better not to do anything.

And all this time we benighted American Episcopalians thought that being Anglican was a Good Thing.

ReplyDeleteHallo, Ignorant Yank here---

ReplyDeleteCould you explain to me (briefly) *WHY* Parliament objected to BCP/Biblical revisions? Thanks!

JCF,

ReplyDeleteNow's that a more difficult question. The long history was that the Church has been governed by statute since its beginning with courts interpreting and enforcing those laws. Every aspect of the government of the church went through Parliament.

The church liked this - they were the spiritual dimension of the state and integral, if junior, in the constitution. The CofE was the 'national' church in several meanings. (You can imagine what this looked like to Catholics and Dissenters.)

From the 1850s / 1860s the Convocations (gatherings of clergy) were restarted (they had been shut down in 1717, which is another story). This was the beginning of a programme for church members to govern themselves (and therefore implicitly acknowledging the CofE was now one denomination amongst many rather than the the church from which the rest dissented).

Lay people had a formal role in the government of the church from 1919 - but parliament continued to think of itself as guardian of the rights of the laity against any incursion by the clergy.

A)the 1927/28 conflict. There had been an extensive consultation process and the proposed book had overwhelming assent in the Church Assembly. But it didn't suit the harder line protestant evangelicals (the catholic party were dominant at the time). The evangelicals mounted a public campaign which swayed parliament.

B) 1960s - 1970s. again the relationship between church and state was being altered, this time to the church's benefit. The key change was that parliament allowed the church to carve out space in which it made its own decisions and didn't have to refer every detail to parliament. Some MPs complained in 1974 that they had been conned because the discretion allowed to the church was only meant to be temporary (the MPs were right, they had been conned). But they were a minority, most MPs were happy to hand over power and no longer wanted to control the church.

The state continues to hang on to many powers but little by little it steadily cedes them to the church.

The key power (and one which the Covenant will exacerbate) is the appointment of bishops. Here the government (not parliament) holds the power and they are only letting go one finger at a time.

You understand that so is so brief as to be a travesty, but I hope it helps.

JCF - answer part 2:

ReplyDeleteA)the 1927/28 conflict. There had been an extensive consultation process and the proposed book had overwhelming assent in the Church Assembly. But it didn't suit the harder line protestant evangelicals (the catholic party were dominant at the time). The evangelicals mounted a public campaign which swayed parliament.

B) 1960s - 1970s. again the relationship between church and state was being altered, this time to the church's benefit. The key change was that parliament allowed the church to carve out space in which it made its own decisions and didn't have to refer every detail to parliament. Some MPs complained in 1974 that they had been conned because the discretion allowed to the church was only meant to be temporary (the MPs were right, they had been conned). But they were a minority, most MPs were happy to hand over power and no longer wanted to control the church.

The state continues to hang on to many powers but little by little it steadily cedes them to the church.

The key power (and one which the Covenant will exacerbate) is the appointment of bishops. Here the government (not parliament) holds the power and they are only letting go one finger at a time.

You understand that so is so brief as to be a travesty, but I hope it helps.