|

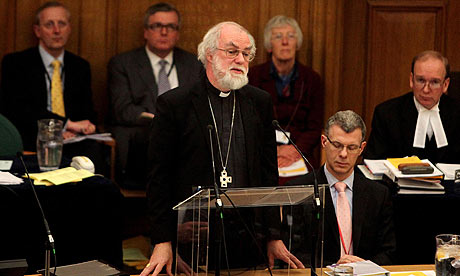

| Archbishop Drexel Gomez |

Please note the date: 2001. Two years before Gene Robinson (wikipedia) was consecrated Bishop of New Hampshire.

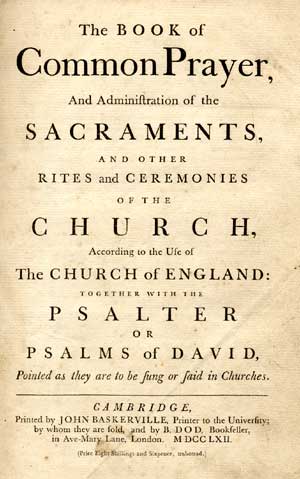

To Mend the Net is a collection of essays with a conservative prescription for the reform of the Anglican Communion. It is not available on the net.

(References below are to paragraph numbers)

The editors' focus was on The Episcopal Church's disregard of the Lambeth 1.10 resolution on sexuality, TEC's decision to monitor progress towards women's ordination in all dioceses, and the equal valuing of marriage and non-marital sexual relations within the Church (1.8) though the valuation of homosexuality within the church was their particular horror (1.6).

Amongst other things the book prescribes:

- 'Enhanced Responsibility' for the Primates' Meeting (as commended by Lambeth 1998, Resolution III.6). This was central to the book's programme. (1.2)

- The 'need to be clear what kind of new practices can be accepted into a process of open reception, how necessary openness can be guaranteed, and how a proper collegiality among Anglican bishops can be restored when it is eroded or broken' (1.8)

- 'Some may be tempted to imagine that democratic structures linked with democratic values will sole our problems. Instead ...' [we choose] 'truth and holiness of life' 'We want to allow the authoritative Scriptures to speak into and redeem our Church and our world and we refuse to relativise or domesticate the Word of God.' (1.10) (See an earlier post, A Richer Covenant)

- They claimed no brief to put a legislative structure above Provinces, but espoused 'the exercise of a form of political authority at the international level.' (1.11)

- 'Genuine collegiality will normally require a minority to respect decisions supported by a majority of Primates.' Experiment in 'doctrine, discipline or ethics' would need 'a consensus or a very substantial majority of Primates' (2.2)

The Exercise of Enhanced Responsibility was summarised as:

- Self Examination led by Primates' personal example (3.1)

- Education: promoted by Primates who should also 'specify the limits of diversity and the frame of reference of provincial autonomy.' (3.2)

- Advanced Sharing: especially sharing initiatives with one another in advance of implementation (3.3)

- Preparation of Guidelines: if a significant minority of Primates disagree with the proposed initiative it should not proceed. If such advice is ignored then 'guidelines' should 'address the situation created and identify its remedy.' (3.4)

- Godly Admonition: the 'guidelines' would be sent to the errant province or diocese [to address the issue of 'local' action allowed but not authorized by a Province] for approval and acceptance. 'This step would be taken with a very positive intent.' (3.5)

- Observer status: if the admonition was not heeded the Archbishop of Canterbury would demote the recalcitrant body from member to observer on international Anglican bodies. (3.6)

- Continuing Evangelization: the Archbishop of Canterbury would also be asked to authorize 'appropriate means of evangelization, pastoral care and episcopal oversight' of the offending body. (3.7)

- New Jurisdiction: And if resistance continued the Archbishop of Canterbury would be advised how to set up a new jurisdiction to replace the offending body as the legitimate Anglican entity in that geographical area. (3.8) The 'intransigent body' would be suspended. (3.8)

- Primates' Commission: a standing commission to assist the Archbishop of Canterbury would be established 'to the furtherance of priorities in mission and the re-ordering in cases of disorder.' (3.9)

What remains in the Covenant?

Drexel Gomez was not chosen to chair the Covenant Design Group as a neutral chair. His views of the present and future of the Communion were well known and the Archbishop of Canterbury must have chosen him with this in mind.

Most obviously the proposal to place the Primates' Meeting at the heart of the response to conflict has vanished. Instead the Standing Committee of the Anglican Communion has been given the equivalent responsibility. This must be a bitter blow to Archbishop Gomez who regarded the Anglican Communion office and its officers as little more than the agents of the compromised, wealthy western church. The Primates' Commission has died too.

Most obviously the proposal to place the Primates' Meeting at the heart of the response to conflict has vanished. Instead the Standing Committee of the Anglican Communion has been given the equivalent responsibility. This must be a bitter blow to Archbishop Gomez who regarded the Anglican Communion office and its officers as little more than the agents of the compromised, wealthy western church. The Primates' Commission has died too.

The Covenant is, however, a mechanism to specify the limits of diversity and it intends to be the frame of reference of provincial autonomy. Its proposal for an officer in every Province is explicitly to ensure advance sharing of possible areas of conflict. Similarly the preparation of 'guidelines' (a strange term for the task) and admonition have been refined and are built into the Covenant mechanisms. So too is the possibility demoting offending Provinces within the international organs of the Communion.

The Covenant does not purport to intervene below the level of the Province - but it is a very live question. Kenneth Kearon raised it in relation to possible action against the Anglican Church of Canada, citing the Windsor Continuation Group Report para 48. Canadians (and others) raise it against the Church of England. Consider the Diocese of Sydney.

The formal authorization of intrusion by one Province into another's jurisdiction (Continuing Evangelization) and the creation of new, replacement, jurisdictions are more worrying. So far as I know these are not on the agenda.

But what would happen if the the Covenant is signed and TEC and Canada are expelled? I'll bet somebody's been thinking it through, and I'll bet these options are still on the table.