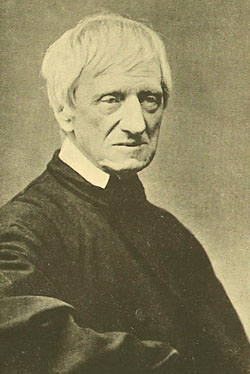

Fr Bryghton Mankhaka on his wedding day

Fr Bryghton Mankhaka on his wedding dayThe tragic death of Father Bright Mankhka, a young Malawian priest in the Diocese of Lake Malawi, on 1st December following a serious road accident, has revealed a callous approach to a man who has faithfully served the Anglican Church as a priest over many years.

ANGLICAN-INFORMATION have received a number of reports about this tragic case of vengeful action which we report as follows:

Bright Mankhaka’s funeral took place on 2nd December where he was buried outside his home church (a church he helped to build) in Bumphula, Ntchisi. A correspondent writes, “many people from all walks of life came to pay their last respects to Fr Bright and to console his young widow Gertrude. He was described as humble, hard-working and dedicated to God’s will.”

However, prior to his death internal political squabbling had led to a star chamber report condemning Fr Bright without it seems any evidence or reason. Dated 27th September 2010, a group of priests under the instruction of the new Bishop of Lake Malawi, Francis Kaulanda, produced the following originally secret report leaked to us and now widely available in the diocese:

‘A report on Rev. Bryghton Mankhaka

Lord Bishop Francis Kaulanda, as per your instructions that we, Canon A.M. Mkoko, Venerable Machemba, Venerable F. Dzantenge, Venerable M. Chilase, Venerable Gumbwa, Rev Fr. S. Matumbo and Canon Christopher Mwawa; interviewed the said priest, I am pleased to present to you the panel’s observations as follows:

i. He is a problem of problems

ii. He has no repentant heart

iii. He is not ready for the priesthood

iv. He is not sure of himself

v. He is not ready to abide by the Canonical obedience

vi. He has shown no remorse

vii. He is not ready to return [the diocesan] motorbike

Recommendations

He is not fit to be hired as priest in this Diocese or elsewhere

Rev’d Canon Christopher K. Mwawa

Chairman of the Panel’

ANGLICAN-INFORMATION observes that it would be hard to find such a shoddy piece of unqualified criticism anywhere. As a report it says nothing of the background or reasons for the seven accusations levelled against Mankhaka and rests essentially as a work of malicious libel. It is astonishing that Bishop Francis Kaulanda has accepted it.

We understand that it was effected during the two week long period that Fr Bright lay unconscious in hospital on life-support and led to the shockingly uncharitable circumstances surrounding the subsequent attempt to bury Fr Bright as a non-religious layman.

A correspondent writes: “Bright’s tragedy has opened up clandestine devilish machinations of some priests of the Diocese of Lake Malawi. When the accident happened we informed the Diocesan Chaplain … he came to see Fr Bright on a Wednesday, after the accident which happened on Monday evening. I understand that the Bishop came to see him on the following Thursday (he has otherwise been in the U.K. including during the time of the funeral). However, we were surprised that the following Sunday no announcement was made or even a mention of him in the prayers.

The Diocesan Secretary refused to offer any kind of support for Fr Bright during his hospitalization or his funeral, saying ‘as a diocese we do not know him as a priest and he must be buried as laity’.

We have seen the Report of the Panel and this has surprised many members of the Church because they did not expect such heavy handedness to be given to a fellow priest who has committed no crime … the diocese has disowned him and only a few personal friends have been to see him. It is very unfortunate as the new Bishop (Francis Kaulanda) promised the Church a new beginning and to bury all past differences ... there are elements that want divisions to continue and are playing the tribal card in church. Now it is Likoma vs Ntchisi and Nkhota-kota etc. It is very pathetic to say the least. Fr Bright was victimised.”

ANGLICAN-INFORMATION notes that another correspondent writes: “In an act of compassion some of Fr Bright’s fellow priests debated the decision of the Report Committee and agreed (bravely) to bury him with the honours of an ordained Priest of the Anglican Church and he was interred as such. They had to open the casket to dress him in his priestly attire.”

So we sadly report another disgraceful picture from the Diocese of Lake Malawi, Province of Central Africa, of hard-hearted, vindictive and unchristian action meted out to a man lying on a life support machine for no reason other than that he had fallen out with the ruling elite.

A full explanation from Bishop Francis Kaulanda is now required.

Want to have your say? Comment below

or visit

our companion blogsite:

http://anglican-information.blogspot.com

.jpg)

%231%23.jpg)